Saturday 26 August 2017

Tuesday 25 July 2017

Flax Bourton, North Somerset

There is a rule of Sculpture Seeking, viz. that if you come to a T junction in a village, you are more likely to take the direction away from the church you're looking for, regardless of how much logic and deliberation you apply. So it was when we finally rolled into Flax Bourton (that we had already been lost was entirely down to my overconfidence in navigating roads out of Bristol).

So when we arrived at the church on this hot day I was already a bit flustered and irritable. The church is right on the main road - probably the closest to a road that we've ever seen. It's got a wall built in front of the door so you can't walk out into the juggernauts (and previously the horses and carriages). Someone has paid for a rather nice glass door to seal the porch off from the noise and pollution. Seeing this, I foolishly thought that it might mean a warm welcome.

No, it didn't. The door was locked. I could lean on the glass and squint under my spread fingers to try and look in without reflections. I could even see the carving. But the door was locked.

I just want to ask, WHY? If you don't want people to steal all the presumed gold candlesticks in the church, why not lock them away like all the other churches we visit? But even if you lock the church itself, why can't people even get into the porch? Is Flax Bourton really the centre of an international crime ring focused on church porches? No-one can even get into the porch to read the noticeboard. I know I'm a heathen and you might only want to let in good members of the congregation that come to services on a Sunday - fair enough. But mightn't Christians want to pop in at other times?

I was disappointed.

We went to the stone circles at Stanton Drew instead. They were fully accessible.

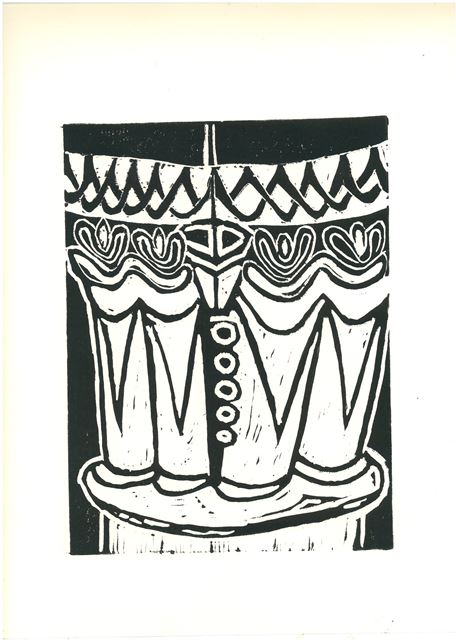

You can see photos on Deborah Harvey's blog. She gets a bit carried away and calls them Saxon - I think as they match so many things we've seen, they're almost certainly Norman. She shows there are more lovely carvings inside the church - not least a cat and a winged legless dragon (these are also misbilled as Saxon). The latter is the first we'd have seen in my recollection. I think it's called an Amphiptere. It would have been an exciting moment. Here's a picture of one to make up for all that disappointment.

So when we arrived at the church on this hot day I was already a bit flustered and irritable. The church is right on the main road - probably the closest to a road that we've ever seen. It's got a wall built in front of the door so you can't walk out into the juggernauts (and previously the horses and carriages). Someone has paid for a rather nice glass door to seal the porch off from the noise and pollution. Seeing this, I foolishly thought that it might mean a warm welcome.

No, it didn't. The door was locked. I could lean on the glass and squint under my spread fingers to try and look in without reflections. I could even see the carving. But the door was locked.

I just want to ask, WHY? If you don't want people to steal all the presumed gold candlesticks in the church, why not lock them away like all the other churches we visit? But even if you lock the church itself, why can't people even get into the porch? Is Flax Bourton really the centre of an international crime ring focused on church porches? No-one can even get into the porch to read the noticeboard. I know I'm a heathen and you might only want to let in good members of the congregation that come to services on a Sunday - fair enough. But mightn't Christians want to pop in at other times?

I was disappointed.

We went to the stone circles at Stanton Drew instead. They were fully accessible.

You can see photos on Deborah Harvey's blog. She gets a bit carried away and calls them Saxon - I think as they match so many things we've seen, they're almost certainly Norman. She shows there are more lovely carvings inside the church - not least a cat and a winged legless dragon (these are also misbilled as Saxon). The latter is the first we'd have seen in my recollection. I think it's called an Amphiptere. It would have been an exciting moment. Here's a picture of one to make up for all that disappointment.

|

| From Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art by J Vineycomb. |

Location:

Flax Bourton, Bristol BS48, UK

Bristol cathedral

|

| CC unicorn by Anders Sandberg |

After a delicious lunch at the Watershed, B and I hauled ourselves up the slope to the cathedral in Bristol. The square outside is home to two amazing gold unicorns. It's not every day that you get to see even one gold unicorn. But here are two, raising their front legs in a very lively pose.

There's a lot of unicorn imagery about at the moment. They seem very popular. And rightly so. But I'd like to point out something about them that I found out while trying to track down what a winged but legless dragon is called (see Flax Bourton) - it's from the same book, 'Fictitious and Symbolic Creatures in Art'. You can't quite see on the photo above, but look elsewhere (eg on Urbina Vinos) and you will distinctly see the cloven hooves! Oh no, unicorns don't have hooves like horses. They have feet like a stag. Don't ask me why though. It's just how they roll.

But we weren't there to see the unicorns. We were there to view the Romanesque architecture.

Labels:

Anglo Saxon,

Bristol,

carving,

Norman,

Romanesque,

sculpture

Location:

Bristol, UK

Monkton Farleigh, Wiltshire

|

| copyright Rhiannon 2017 |

Friday 9 June 2017

Monday 29 May 2017

Saturday 20 May 2017

Cold Aston, Gloucestershire

We don't often meet people at the churches on our travels, and when we do they're generally welcoming and either we exchange pleasantries or have a little chat about our shared interest in the building. As we stood drawing in the porch at Cold Aston, though, a long trail of tinies from the adjacent school trooped into the church and took their places in the pews. I shouldn't mind this, should I. It's an example of the church Actually Being Used. But I didn't like it. Now I can't say I know much about children, but I do know that I was once one of them. And when I was five I had a soft, receptive, gently forming brain. I seem to remember I liked filling it with dinosaurs and trips to the swings.

It's not that I don't think that children should get a education in Behaving Nicely to their Fellow Man. Of course a bit of moral guidance is the way to encourage a nice society where we all help each other and think about others. But I just thought it was very odd that they were shuffled into the church, as though talking about being helpful or kind or whatever it was, couldn't be done in an ordinary setting. As though by going in the church, God would be watching. The teacher (she was wearing a football strip, bizarrely) seemed to switch between that patronising slow sing-song voice some people use with small children, and then swooping on individuals to berate them for their fidgiting or previous misdemeanours. I thought the whole thing was rather creepy, it didn't sit well with me.

I don't know what I'm trying to say really. But it didn't seem quite right to be moulding such small children's minds using the building in that way. It wasn't the same as going there of a Sunday with one's parents to listen to the vicar.

Anyway. There were some interesting bits of carving at Cold Aston. The tympanum was an all-over repetitive pattern (I admit photoshop has helped me with the above depiction) with some rather familiar style weaving foliage underneath. This was very well preserved and rather nice.

Also there seeemed to be a bit of knotwork in the porch - one assumes Anglo Saxon. You can see the collection of bits and pieces here on Britain Express. I always like to see a bit of Saxon knotwork, and because they're quite a challenge to draw, they're always especially satisfying to have a go at. Various descriptions on the internet mention "entwined serpents" but I fear this is overly optimistic. B and I have seen quite a few serpenty examples and this one wasn't doing it for us. But we both felt that there might be little clasped hands - as we independently came to this conclusion I set some store by it.

There was also a Maperton-esque little head, which B drew.

Labels:

Anglo-Saxon,

architecture,

carving,

church,

Cold Aston,

doorway,

Gloucestershire,

head,

knotwork,

Norman,

Romanesque,

sculpture,

tympanum

Location:

Cold Aston, Cheltenham GL54, UK

Windrush, Gloucestershire

Windrush is an excellently romantic name for a village (and the stream that runs through it). It seemed to be another well-heeled Cotswold spot. And maybe it's a good job that it's well-heeled, because some money has been recently poured into the renovation of the church - specifically, its amazing doorway. Because the door here is surrounded by not one, but two rounds of beakheads. It's a first for us. I can't think there can be many examples of the Double Beakhead in the country. So it's excellent to see it's being looked after.

The beakheads have just been cleaned. And they've been cleaned very thoroughly. In fact almost so thoroughly that they looked quite odd. But I guess they can now carry on for another thousand years. They're on the south side of the chuch, and have a small roof over them to protect them a little from the rain, but nothing major. Perhaps their south-facing aspect has been what's saved them for so long. It would be nice if they had a porch. But they're so interestingly animated that in a silly way I quite like that they can see out.

SSH Conservation carried out the work. You can see photos of the Before and After on their website. You can see how bright and stark the doorway is now - as it would have done when it was first carved, an interesting thought. The faces are a bit different from the beakheads we've seen before. B called them menacing, as I recall. They've certainly got quite intense expressions on their beaky faces. Their almond-shaped eyes remind me a bit of insects or aliens! The characters are quite varied. They don't all have beaks to cling onto the roll of the doorway. The drawing above shows two non-beaky ones.

A silly thing happened as I admired the doorway - I took a step backward and promptly fell up the steps that lead down to it. An unusual feature, in my defence. I just sat down on my arse and lay there, it wasn't dignified but it was quite funny. I hope it at least gave the beakheads something amusing and unusual to see.

The beakheads have just been cleaned. And they've been cleaned very thoroughly. In fact almost so thoroughly that they looked quite odd. But I guess they can now carry on for another thousand years. They're on the south side of the chuch, and have a small roof over them to protect them a little from the rain, but nothing major. Perhaps their south-facing aspect has been what's saved them for so long. It would be nice if they had a porch. But they're so interestingly animated that in a silly way I quite like that they can see out.

SSH Conservation carried out the work. You can see photos of the Before and After on their website. You can see how bright and stark the doorway is now - as it would have done when it was first carved, an interesting thought. The faces are a bit different from the beakheads we've seen before. B called them menacing, as I recall. They've certainly got quite intense expressions on their beaky faces. Their almond-shaped eyes remind me a bit of insects or aliens! The characters are quite varied. They don't all have beaks to cling onto the roll of the doorway. The drawing above shows two non-beaky ones.

A silly thing happened as I admired the doorway - I took a step backward and promptly fell up the steps that lead down to it. An unusual feature, in my defence. I just sat down on my arse and lay there, it wasn't dignified but it was quite funny. I hope it at least gave the beakheads something amusing and unusual to see.

Labels:

beakhead,

carving,

church,

doorway,

Gloucestershire,

Norman,

Romanesque,

sculpture,

Windrush

Location:

Windrush, UK

Bibury, Gloucestershire

Labels:

Anglo-Saxon,

Bibury,

carving,

church,

Gloucestershire,

Romanesque,

Saxon

Location:

Bibury, Cirencester GL7, UK

Wroughton, Wiltshire

Labels:

church,

doorway,

dragon,

font,

headstop,

Norman,

Romanesque,

sculpture,

Wiltshire,

Wroughton

Location:

Wroughton, Swindon SN4, UK

Bromham, Wiltshire

Labels:

Bromham,

church,

norman architecture,

Wiltshire

Location:

Bromham, Chippenham SN15, UK

Bathampton, Bath and North-East Somerset

Labels:

Bathampton,

carving,

church,

Norman,

North East Somerset,

Romanesque,

sculpture

Location:

Bathampton, Bath, UK

Sunday 12 March 2017

Priston, North-East Somerset

Labels:

capital,

church,

neonorman,

Norman carving,

North-East Somerset,

Priston

Location:

Priston Village, Bath BA2, UK

Radstock, North-East Somerset

Labels:

church,

North-East Somerset,

Radstock

Location:

Radstock BA3, UK

Kilmersdon, Somerset

The lych-gate at Kilmersdon was the perfect place for a picnic. It's disappointing in a way, but we now feel we must appear sufficiently middle-aged looking that we don't attract disapproving looks from passing locals. So not looking like a youf does have its advantages. B had expertly prepared the picnic and it included boiled eggs (so I felt like Columbo) and highly carameliferous wafers. Plus tea in a flask. You'd never get that level of care from me. But the hot drink was greatly appreciated.

We soon found out that the door was resolutely bolted. This is always immensely disappointing and bemusing, particularly in a country village where the risk of people stealing damp hymn books and charity leaflets would seem to be particularly low, but the likelihood of ramblers wanting to pop in and leave a quid or two would seem to be particularly high. However. I suspected that there would be lots of interesting things outside.

Pevsner just says "Much Norman evidence" but doesn't particularly mention that there are carved corbels on the south side of the church, and surely they're Norman. I think we know a Norman corbel when we see it these days. They always have a nice simple style and might include animals or people Doing Things.

There were some great big medieval gargoyles on the north side of the church, really quite excellent. I tried to draw one but the angle made it difficult (I say this but B seemed to manage perfectly well). There's much to see and appreciate here.

We soon found out that the door was resolutely bolted. This is always immensely disappointing and bemusing, particularly in a country village where the risk of people stealing damp hymn books and charity leaflets would seem to be particularly low, but the likelihood of ramblers wanting to pop in and leave a quid or two would seem to be particularly high. However. I suspected that there would be lots of interesting things outside.

Pevsner just says "Much Norman evidence" but doesn't particularly mention that there are carved corbels on the south side of the church, and surely they're Norman. I think we know a Norman corbel when we see it these days. They always have a nice simple style and might include animals or people Doing Things.

There were some great big medieval gargoyles on the north side of the church, really quite excellent. I tried to draw one but the angle made it difficult (I say this but B seemed to manage perfectly well). There's much to see and appreciate here.

Labels:

church,

corbel,

Kilmersdon,

medieval,

Norman carving,

Somerset

Location:

Kilmersdon, Radstock BA3, UK

Hemington, North Somerset

Hemington didn't seem to be hugely bigger than Hardington Bampfylde, but its church is just massive. It's got aisles, and a sort of chapel open to the south side of the altar. The latter was where we found the excellent Norman font with its petally scallops. Pevsner calls the decoration 'lobes'. Sometimes I think he just didn't care about Norman fonts at all :) But I mustn't feel too irritated by him as his books are essentially the reason B and I have found so many interesting places to visit. And at least we have the luxury of enjoying wherever we go. His explorations for the books must have turned into sheer slog. Monetarily rewarded slog of course. With the opportunity for the occasional sarcastic remark. But slog nonetheless. "Right let's go, we've got 15 more to do before teatime."

The chancel arch is Norman in style too, but very sharply carved, to the extent where we were doubting its age. It's not got the personalised soft variety of the carving of the font. But I was kind of swung by the slight asymmetricalness of the design of the capitals - the pairs to left and right don't quite match. Plus there are traces of bright paint on them - does that not indicate their Normanness? I don't know. The age of the foot of the columns seems easier to acknowledge, again asymmetrical with chevrons on one of them. And what's that... yep at the bottom of one of the ones on the left, there's a strange little head. It reminded us a little of the "minute face" at Maperton.

What an unexpected and curious thing. What a nice thing that the carver of the columns stole the opportunity to add this little character. It rather humanises the otherwise quite severe archway. What did it mean to people of the time I wonder? It's tempting to read something un-Christian into it, something to do with spirits being in everything around us. But you can't imagine that would have been entertained at all, though is it possible that Evil spirits might be lurking about. I don't know. I liked the little face though. I gave it a proper dusting. In fact there were lots of interesting carvings in Hemington, a whole row of them along the south aisle, though not as old.

And another thing we appreciated about Hemington was its toilet, unlocked. Such a boon to the fonting traveller. I'm not kidding. It was also nice to have a look through the ferns in the little well opposite the church. The watery theme continued as we drove up out of the village and spotted water pouring out of the roadside at the top of the hill. We had to stop. It was a liverwort jungle, and with such a soothing sound.

The chancel arch is Norman in style too, but very sharply carved, to the extent where we were doubting its age. It's not got the personalised soft variety of the carving of the font. But I was kind of swung by the slight asymmetricalness of the design of the capitals - the pairs to left and right don't quite match. Plus there are traces of bright paint on them - does that not indicate their Normanness? I don't know. The age of the foot of the columns seems easier to acknowledge, again asymmetrical with chevrons on one of them. And what's that... yep at the bottom of one of the ones on the left, there's a strange little head. It reminded us a little of the "minute face" at Maperton.

What an unexpected and curious thing. What a nice thing that the carver of the columns stole the opportunity to add this little character. It rather humanises the otherwise quite severe archway. What did it mean to people of the time I wonder? It's tempting to read something un-Christian into it, something to do with spirits being in everything around us. But you can't imagine that would have been entertained at all, though is it possible that Evil spirits might be lurking about. I don't know. I liked the little face though. I gave it a proper dusting. In fact there were lots of interesting carvings in Hemington, a whole row of them along the south aisle, though not as old.

And another thing we appreciated about Hemington was its toilet, unlocked. Such a boon to the fonting traveller. I'm not kidding. It was also nice to have a look through the ferns in the little well opposite the church. The watery theme continued as we drove up out of the village and spotted water pouring out of the roadside at the top of the hill. We had to stop. It was a liverwort jungle, and with such a soothing sound.

Labels:

church,

face,

font,

Hemington,

Norman sculpture,

North Somerset,

Romanesque carving

Location:

Hemington, UK

Hardington Bampfylde, North Somerset

If you wanted a journey to epitomise 'Wiltshire Wandering' it could be the one to Hardington Bampfylde (except it's not in Wiltshire of course). What I mean is that it requires scrutiny of the OS map to find this excellently named location. And then we're rumbling along the main road thinking 'is it this little turn? nope... must be the next one... OMG HERE IT IS' with a sudden dash down into a little lane. Followed by the immediate sensation that the busy everyday world is left behind, and now you're properly in the country, with rolling fields and hedges both sides of the narrow road, and the sensation that something interesting lies ahead. Plus, we found ourselves diverting off this road onto a track, heading uphill across dung and into a farmyard. The little church stood amongst the farm buildings. It was an entirely promising sensation. A good place to begin today's wanderings.

The church is owned by the Churches Conservation Trust so there was no trouble opening the door. It had a peaceful damp air and with its Georgian woodwork felt remarkably authentic and unmessed with. The chancel arch looked simple and Norman, and straining a bit to fall outwards. I see Mr Pevsner says it's not medieval. But who knows. He only had his eyes to go on like we did. And it looks pretty good to me, it's certainly the right style, and I don't see anyone aping the Romanesque in the rest of the building, it's all pointy windows. So I'm going for it, personally.

Also in the Norman department was the amazing chunky font. I tried to draw it. The proportions came out wrong in disappointing fashion. When you've got such a simple design, the proportions are everything. It makes you realise what beautiful aesthetic sense these sculptors had nearly a thousand years ago. B and I always love to see another example. I think it's safe to say we're obsessed connoisseurs of them.

Also there were drawings on the wall opposite the door, in red - faces and twirls and vegetation. I wonder how old these are? Clearly it would rather depend on the wall. I wonder if it would ever be possible - maybe not from the style, which you'd imagine would depend a lot on the hand of the artist. But maybe from whatever the paint is derived from, or... I don't know. Anyway I enjoyed trying to copy some of them.

The church is owned by the Churches Conservation Trust so there was no trouble opening the door. It had a peaceful damp air and with its Georgian woodwork felt remarkably authentic and unmessed with. The chancel arch looked simple and Norman, and straining a bit to fall outwards. I see Mr Pevsner says it's not medieval. But who knows. He only had his eyes to go on like we did. And it looks pretty good to me, it's certainly the right style, and I don't see anyone aping the Romanesque in the rest of the building, it's all pointy windows. So I'm going for it, personally.

Also in the Norman department was the amazing chunky font. I tried to draw it. The proportions came out wrong in disappointing fashion. When you've got such a simple design, the proportions are everything. It makes you realise what beautiful aesthetic sense these sculptors had nearly a thousand years ago. B and I always love to see another example. I think it's safe to say we're obsessed connoisseurs of them.

Also there were drawings on the wall opposite the door, in red - faces and twirls and vegetation. I wonder how old these are? Clearly it would rather depend on the wall. I wonder if it would ever be possible - maybe not from the style, which you'd imagine would depend a lot on the hand of the artist. But maybe from whatever the paint is derived from, or... I don't know. Anyway I enjoyed trying to copy some of them.

Monday 6 March 2017

Minstead, Hampshire

|

| Lamb of God from the Minstead font |

|

| Double bodied creature |

|

| Eagles and ? |

|

| Minstead baptism? scene |

Bear with me while I amuse myself, my animation skills are severely last century.

|

| The lamb of god gif. Has there ever been such a thing before in the history of the internet. |

Labels:

church,

font,

Hampshire,

lamb of god,

Minstead,

Norman carving,

Romanesque carving

Location:

Minstead, Lyndhurst SO43, UK

Saturday 4 March 2017

Kelston, North-East Somerset

A week or two ago we tried to visit some churches in North-East Somerset: Bitton and Queen Charlton. But they were both locked up tight. This is always very disappointing and really rather bemusing. Especially when there's no friendly notice about where a key can easily be retrieved (a neighbouring door is always nicer to knock on than a bald list of mobile phone numbers, the owners of which could be anywhere at all).

I've found some additional information about the carvings at nearby Kelston though.

This beautiful fragment of a Saxon cross was found by the late Rector, the Rev. F.J.Poynton, thrown aside amongst the rubbish of the old church at the time of its restoration in 1860. The stone isa n oblong square, and appears to have been in use at some former time as a door-jamb. It measures 2ft. 9in. in length, by 1ft. 3in. in width. When discovered, two of its sides were entirely defaced, and a third so injured that only faint traces of carving were visible at the top. The fourth side was smoothed to a surface with mortar, and had then received several coats of whitewash. It was in this state when Mr. Poynton undertook the removal of this facing, an operation in which he entirely succeeded and thus exposed the original carving to view.

The sculpture is divided by a cable-roll into two parts, and a roll of the same pattern borders it, as in the cross at Bedale, in Yorkshire. In the upper division, which is the larger, is represented two central steps supporting a square, from which spring two stems. The stems are sub-divided, and artistically formed into turning convolutions, each terminal ending in a cordate leaf. Here and there small ovate bodies are introduced in the axils of the branches, which may be taken to mean either buds, or fruit, probably the latter. At no single point do the branches from the two stems unite.

From the resemblance of the design to the figure of a tree, it has been conjectured that it illustrates a rude attempt to portray the Tree of Life, but the presence of the fruit points rather to the other tree in the Garden, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, since the "Tree of the Fall" is not infrequently met with in early religious art, and is sometimes seen displayed in mystic and typical connection with the Cross. Although, in this instance, the rigid form of the Christian symbol is not apparent, yet the accessories of the steps forming a Calvary, and a block for the socket, together with the flexible tracery of the branches are not a little suggestive of the union of the Cross witht he Tree, particularly as we find in some early examples - as that on a slab at Bakewell, Derbyshire - that the distinctive character of the Cross is preserved in the Calvary and stem, while it is lost in the interleaving knotwork that forms the head. The introduction of transitional foliage int o the curved lines of the coil renders this unique fragment one of high interest. The lower division is filled in with the usual form of the endless interlacing knot.

In order to preserve it from injury, Mr. Poynton has had this valuable relic placed inside the Church, fixed in the wall of the chancel on the north side, just exposing the sculptured face in projection. Late 11th Century.

Yes I have been rubbishing some other interpretations of the things we see. But this time maybe I like the idea of the 'steps forming a Calvary' from which the stems emerge. And although two stems rather goes against the theory, perhaps we can just have them as nice planty knotwork.

I've found some additional information about the carvings at nearby Kelston though.

This beautiful fragment of a Saxon cross was found by the late Rector, the Rev. F.J.Poynton, thrown aside amongst the rubbish of the old church at the time of its restoration in 1860. The stone isa n oblong square, and appears to have been in use at some former time as a door-jamb. It measures 2ft. 9in. in length, by 1ft. 3in. in width. When discovered, two of its sides were entirely defaced, and a third so injured that only faint traces of carving were visible at the top. The fourth side was smoothed to a surface with mortar, and had then received several coats of whitewash. It was in this state when Mr. Poynton undertook the removal of this facing, an operation in which he entirely succeeded and thus exposed the original carving to view.

The sculpture is divided by a cable-roll into two parts, and a roll of the same pattern borders it, as in the cross at Bedale, in Yorkshire. In the upper division, which is the larger, is represented two central steps supporting a square, from which spring two stems. The stems are sub-divided, and artistically formed into turning convolutions, each terminal ending in a cordate leaf. Here and there small ovate bodies are introduced in the axils of the branches, which may be taken to mean either buds, or fruit, probably the latter. At no single point do the branches from the two stems unite.

From the resemblance of the design to the figure of a tree, it has been conjectured that it illustrates a rude attempt to portray the Tree of Life, but the presence of the fruit points rather to the other tree in the Garden, the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, since the "Tree of the Fall" is not infrequently met with in early religious art, and is sometimes seen displayed in mystic and typical connection with the Cross. Although, in this instance, the rigid form of the Christian symbol is not apparent, yet the accessories of the steps forming a Calvary, and a block for the socket, together with the flexible tracery of the branches are not a little suggestive of the union of the Cross witht he Tree, particularly as we find in some early examples - as that on a slab at Bakewell, Derbyshire - that the distinctive character of the Cross is preserved in the Calvary and stem, while it is lost in the interleaving knotwork that forms the head. The introduction of transitional foliage int o the curved lines of the coil renders this unique fragment one of high interest. The lower division is filled in with the usual form of the endless interlacing knot.

In order to preserve it from injury, Mr. Poynton has had this valuable relic placed inside the Church, fixed in the wall of the chancel on the north side, just exposing the sculptured face in projection. Late 11th Century.

Yes I have been rubbishing some other interpretations of the things we see. But this time maybe I like the idea of the 'steps forming a Calvary' from which the stems emerge. And although two stems rather goes against the theory, perhaps we can just have them as nice planty knotwork.

Labels:

Anglo Saxon sculpture,

church,

Kelston,

knotwork,

North-East Somerset

Friday 3 March 2017

Tuesday 28 February 2017

Little Langford, Wiltshire

It's not surprising if some of the carvings we visit come with their own folklore. The iconography is often a bit bemusing to the 21st century eye, and I guess it has been for a long while. A lot of the time the "official" explanations in the church aren't terribly convincing as fact. But if you take it as folklore you don't feel obliged to believe it. I've found some tales connected with the lavish carvings at Little Langford.

"There you are," said Pertwood. "One of the treasures of the Wylye valley! There are different opinions as to what the figure of the bishop represents. One version, based on the presence of his staff with its sprouting branch, is that he is St. Aldhelm, and that it was carved when St. Osmund was Bishop of Sarum. If that is correct, the carving was done some time between the years 1078 and 1099. It was St. Osmund who moved St. Aldhelm's remains to Malmesbury.

Another theory is that he is St. Nicholas, patron saint of the Church, with the three balls repeated in pattern as his special emblem."

"It sounds more like the House of Lombard to me," chuckled Gullible.

Pertwood ignored the interruption.

"The three birds on the tree are given as representing three boys whom St. Nicholas restored to life," he went on, "or three souls saved from sin, with the tree representing the Tree of Life.

The oddest interpretation of all, however, is reputed to come from the local rustics. There is a local legend of a girl who went nutting in Grovely Woods. Out of one of the nuts came a large maggot, which she kept and fed until it became large indeed. Then, like an ungrateful dog, the maggot turned round and bit the hand that fed it, and the poor girl died. Your three balls of Lombardy are supposed to be the nuts, the birds and the tree are Grovely Woods, and the Bishop is the Maid."

"What a dreadful tale! How is it supposed to end?"

"Why you have the ending in the wild boar hunt. With fertile imagination, the locals turned the Maggot into a Wild Beast that ate up the Maid, then the villagers came out with their dogs and killed it!"

"Let's go in and have a look at the Church," laughed Gullible, "I can't stand any more of this."

This is from The Warminster and Westbury Journal, 18th January 1952. I had no previous idea, but the House of Lombard is an allusion to pawnbrokers and their symbol of three golden spheres.

In the Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette from the 4th August 1864 (on the occasion of the entirely rebuilt church being reopened) I read:

"The old part of the church was built about the year 1130, the remains of that date being the old door-way and the font. Over the door-way would be seen a figure of St. Nicholas, holding a pastoral staff in his hand, and in the act of giving benediction. Beside this was a tree and three birds, representing, it was supposed, the grain of mustard seed, which was to spring up and become a tree, so that the birds would come and lodge in its branches. Underneath these figures was a boar hunt. Now, Grovely wood was once famous for boar hunting, and there was a field about a mile and a half from Langford which still retained the name as being the place where the last boar was killed in England. Behind St. Nicholas would be seen three stones, representing three urns of gold. [...] Before going further, he might mention that the capitals of the old Norman door-way were pieces of very curious sculpture, which, he expected, referred to the promise of our Lord that the Christian should be able to tread on the adder and the serpent, and which they would find great interest in examining and trying to make out for themselves."

B and I certainly find great interest in examining and trying to make out the carvings for ourselves. But I'd take the rest with a little pinch of salt perhaps. To be honest, I almost don't want to know a definitive truth. Part of the carvings' attraction to me are their unknowableness and Numinosity.

In the name of cultural improvement I looked up this mustard seed business. It's in Matthew 13:31/32: "Another parable put he forth unto them, saying, The kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field: which indeed is the least of all seeds: but when it is grown, it is the greatest among herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches thereof." Well I don't like to quibble, but Jesus obviously wasn't much of a botanist, or he'd have known that a mustard seed doesn't grow into a tree. It grows into that stuff you put in egg sandwiches.

"There you are," said Pertwood. "One of the treasures of the Wylye valley! There are different opinions as to what the figure of the bishop represents. One version, based on the presence of his staff with its sprouting branch, is that he is St. Aldhelm, and that it was carved when St. Osmund was Bishop of Sarum. If that is correct, the carving was done some time between the years 1078 and 1099. It was St. Osmund who moved St. Aldhelm's remains to Malmesbury.

Another theory is that he is St. Nicholas, patron saint of the Church, with the three balls repeated in pattern as his special emblem."

"It sounds more like the House of Lombard to me," chuckled Gullible.

Pertwood ignored the interruption.

"The three birds on the tree are given as representing three boys whom St. Nicholas restored to life," he went on, "or three souls saved from sin, with the tree representing the Tree of Life.

The oddest interpretation of all, however, is reputed to come from the local rustics. There is a local legend of a girl who went nutting in Grovely Woods. Out of one of the nuts came a large maggot, which she kept and fed until it became large indeed. Then, like an ungrateful dog, the maggot turned round and bit the hand that fed it, and the poor girl died. Your three balls of Lombardy are supposed to be the nuts, the birds and the tree are Grovely Woods, and the Bishop is the Maid."

"What a dreadful tale! How is it supposed to end?"

"Why you have the ending in the wild boar hunt. With fertile imagination, the locals turned the Maggot into a Wild Beast that ate up the Maid, then the villagers came out with their dogs and killed it!"

"Let's go in and have a look at the Church," laughed Gullible, "I can't stand any more of this."

This is from The Warminster and Westbury Journal, 18th January 1952. I had no previous idea, but the House of Lombard is an allusion to pawnbrokers and their symbol of three golden spheres.

|

| My interpretation of the tympanum at Little Langford |

"The old part of the church was built about the year 1130, the remains of that date being the old door-way and the font. Over the door-way would be seen a figure of St. Nicholas, holding a pastoral staff in his hand, and in the act of giving benediction. Beside this was a tree and three birds, representing, it was supposed, the grain of mustard seed, which was to spring up and become a tree, so that the birds would come and lodge in its branches. Underneath these figures was a boar hunt. Now, Grovely wood was once famous for boar hunting, and there was a field about a mile and a half from Langford which still retained the name as being the place where the last boar was killed in England. Behind St. Nicholas would be seen three stones, representing three urns of gold. [...] Before going further, he might mention that the capitals of the old Norman door-way were pieces of very curious sculpture, which, he expected, referred to the promise of our Lord that the Christian should be able to tread on the adder and the serpent, and which they would find great interest in examining and trying to make out for themselves."

B and I certainly find great interest in examining and trying to make out the carvings for ourselves. But I'd take the rest with a little pinch of salt perhaps. To be honest, I almost don't want to know a definitive truth. Part of the carvings' attraction to me are their unknowableness and Numinosity.

In the name of cultural improvement I looked up this mustard seed business. It's in Matthew 13:31/32: "Another parable put he forth unto them, saying, The kingdom of heaven is like to a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field: which indeed is the least of all seeds: but when it is grown, it is the greatest among herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches thereof." Well I don't like to quibble, but Jesus obviously wasn't much of a botanist, or he'd have known that a mustard seed doesn't grow into a tree. It grows into that stuff you put in egg sandwiches.

Location:

Little Langford, Salisbury SP3, UK

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)